Our Reserves

Onion Lake Gathering, 1890

An important Makwa Sahgaiehcan leader was Peepeekoot. Peepeekoot was the son of Masuskapoe, Ahtahkakoop’s brother. In 1883, Peepeekoot married Isabella, daughter of Waskitoy, known as “Benjamin Joyful” who was a Headman alongside Ahtahkakoop.

In 1898, Peepeekoot told Canada his father, Masuskapoe signed Treaty 6 at Fort Pitt in 1876. Peepeekoot said he and his community of Makwa Sahgaiehcan were owed their own reserve.

Peepeekoot was not alone. Other Makwa Sahgaiehcan people also requested an independent reserve over and over again. Some Makwa Sahgaiehcan people who lived on the Onion Lake reserve or Island Lake (Ministikwan) told Canada they wanted their own reserve. At a meeting in 1905 at Ministikwan, Canada made note that:

“Loon Lake Band members participated in Island Lake Band’s request for an independent reserve.”

Again, in 1912 at Onion Lake, Makwa Sahgaiehcan peoples wrote to Canada to say about 15 families living at Onion Lake wanted our “own reserve.”

In 1913, Canada approached Crees at Waterhen to try and get them to ‘take treaty’. Canada reported they found Waterhen’s numbers had grown due to “a small number of non-treaty Indians from Loon Lake.” Canada also acknowledges the “stragglers” from Loon Lake were not welcomed by Waterhen Lake.

Canada’s plan of placing all Crees on one large reserve was not supported by Cree people themselves. Canada’s plan was falling apart.

In 1914, Canada held another meeting at Onion Lake.

Makwa Sahgaiehcan people explained what they expected out of a treaty with Canada. We wanted an entire township as our reserve. Privately, Canada knew they would never give us a reserve that big, and they needed to hide that from us.

Canada gossiped behind our backs and said:

“No good can result from the Indians imagining they have a very great area.”

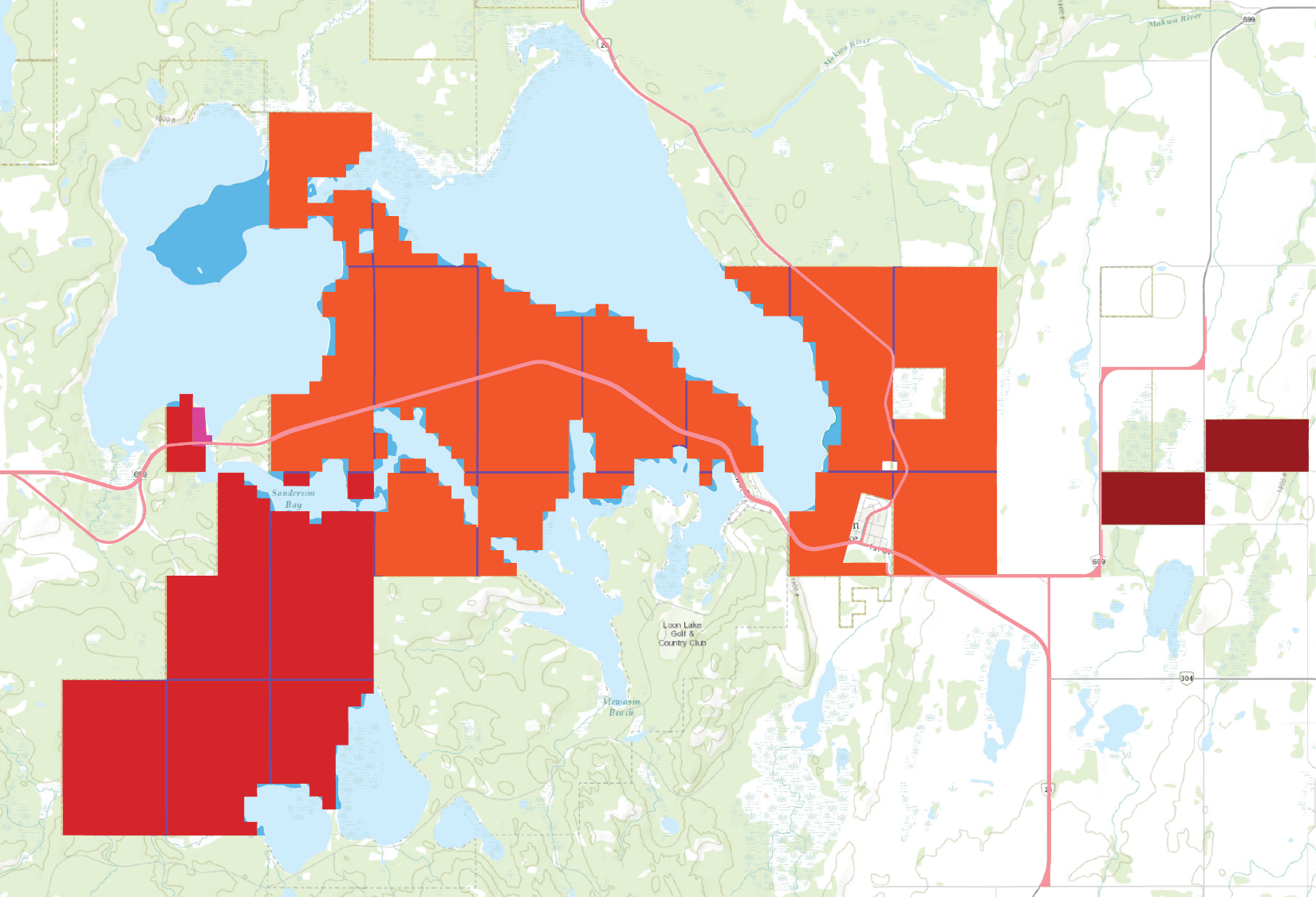

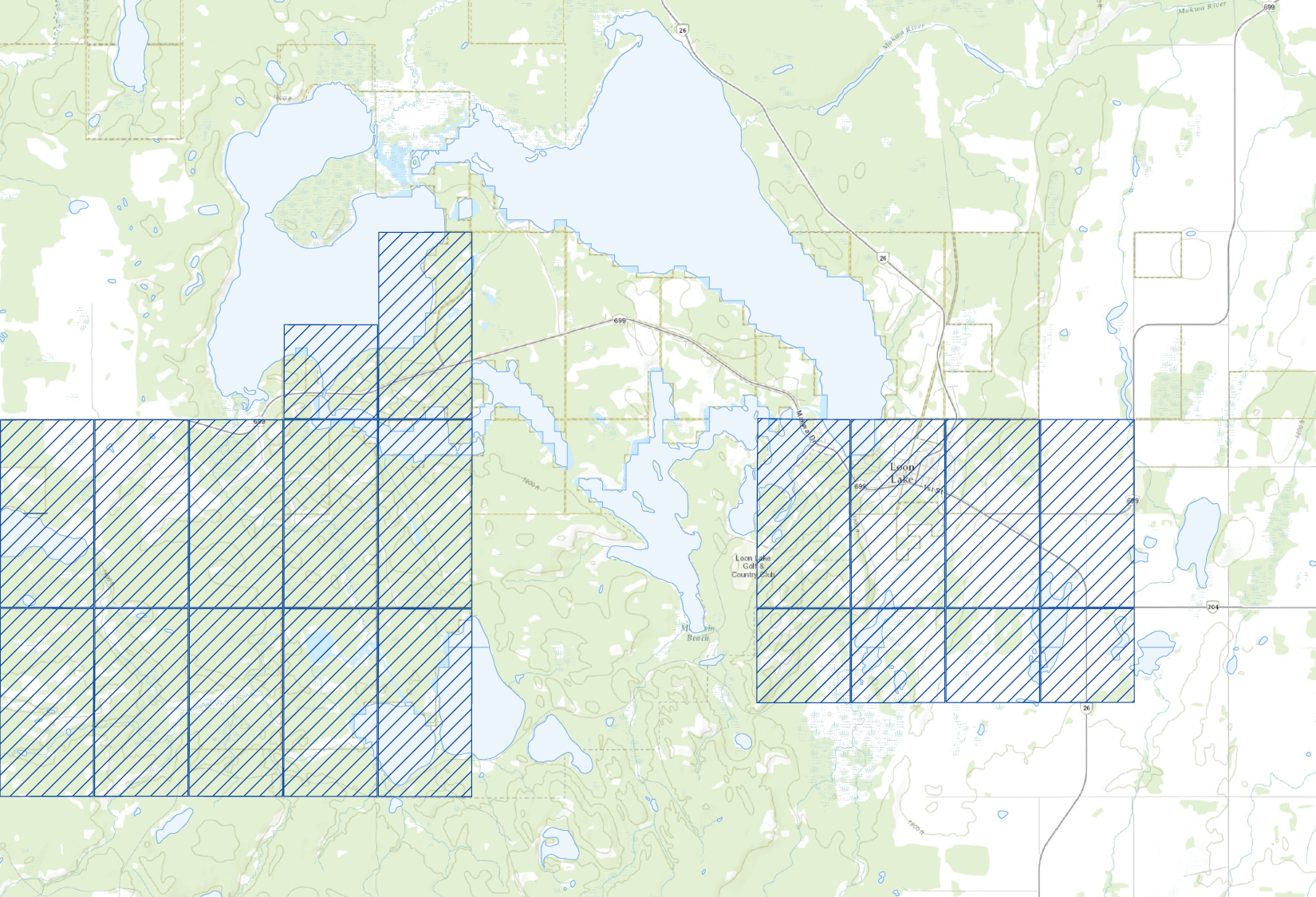

Behind the scenes, Canada identified potential areas for the reserve at Makwa Lake. The area they identified wasn’t one big reserve. It was two parcels that weren’t connected. One area was around Goose Lake, and another south of Makwa Lake.

1915 Temporary Reserves

Canada told us we would only get 128 acres per person, which was the amount written into Treaty 6. We didn’t know that Canada was giving away land to white settlers for free.

By February 1916, Canada was ready to acknowledge only 40 Makwa Sahgaiehcan people as Treaty Indians. They also told us we would need to have more Makwa Sahgaiehcan people want to take treaty to even have our own reserve.

Every chance they got, Makwa Sahgaiehcan people stood up at meetings and told Canada we wanted our own reserve in our area.

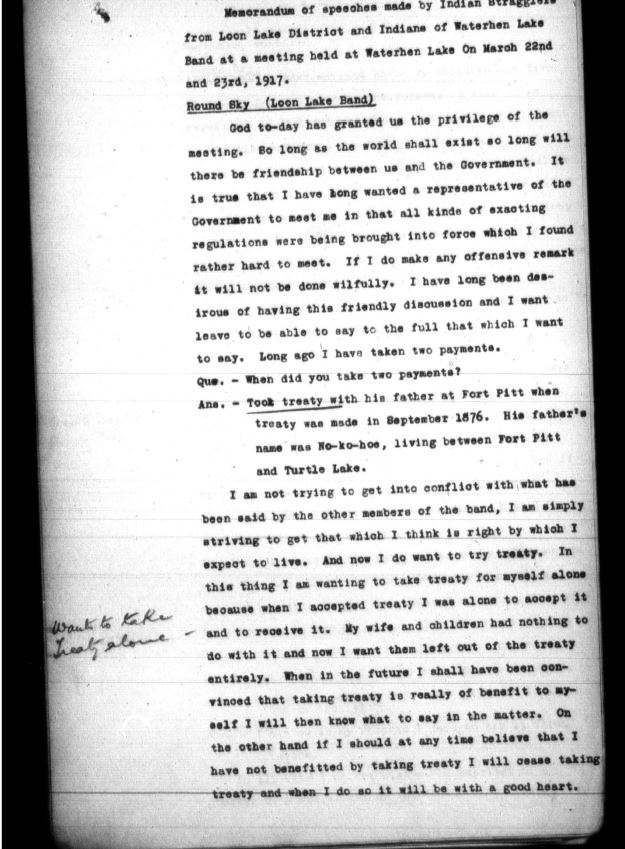

In 1917 at a meeting at Waterhen, Otustiwayo told Canada he “was born and brought up at Loon Lake” but had never been “a member of that band that accepted that agreement.”

Meeting with Canada, 1917

Roundsky, identified himself as the head of a family of four from the Loon Lake “Stragglers” and said he had initially ‘taken treaty’ with his father, Nokohoe, at Fort Pitt in 1876. He was also clear about his expectations for the treaty:

“I wish to be permitted to pick out and choose the land I shall want. I will also ask for land where I can get hay, also land where I can get timber. I also want the privilege granted to me to be allowed to continue and follow that kind of worship which has been mine and will be as long as time. I also want the privilege of being able to kill all the game that I shall require for my living as long as the last game is to be found. In the same way I crave permission from the Government to kill fish and furred animals for my own living”

Finally, in 1919, Canada was ready to set aside a reserve for us.

We wanted to be around the 7 lakes, including Goose Lake. We knew there was good fishing. There were several families important to this event. The families of Kytweyhat, Cheenanow (Partridge), Wacaskosit (Cantre), Kayakosis and Mitsuing (Fineblanket), and Soniywa-okimaw (Money Chief) all played a part in the creation of the Makwa Sahgaiehcan reserves.

Our reserve was created very late, much later than the other reserves in Treaty 6.

Forty-two members of the ‘Loon Lake Band’ entered or adhered to Treaty 6. Each person was paid a treaty annuity of $12.67. Canada came up with an amount of each $12.67, but we believed each person was owned backpay of treaty monies since 1876. We believed we were shortchanged again.

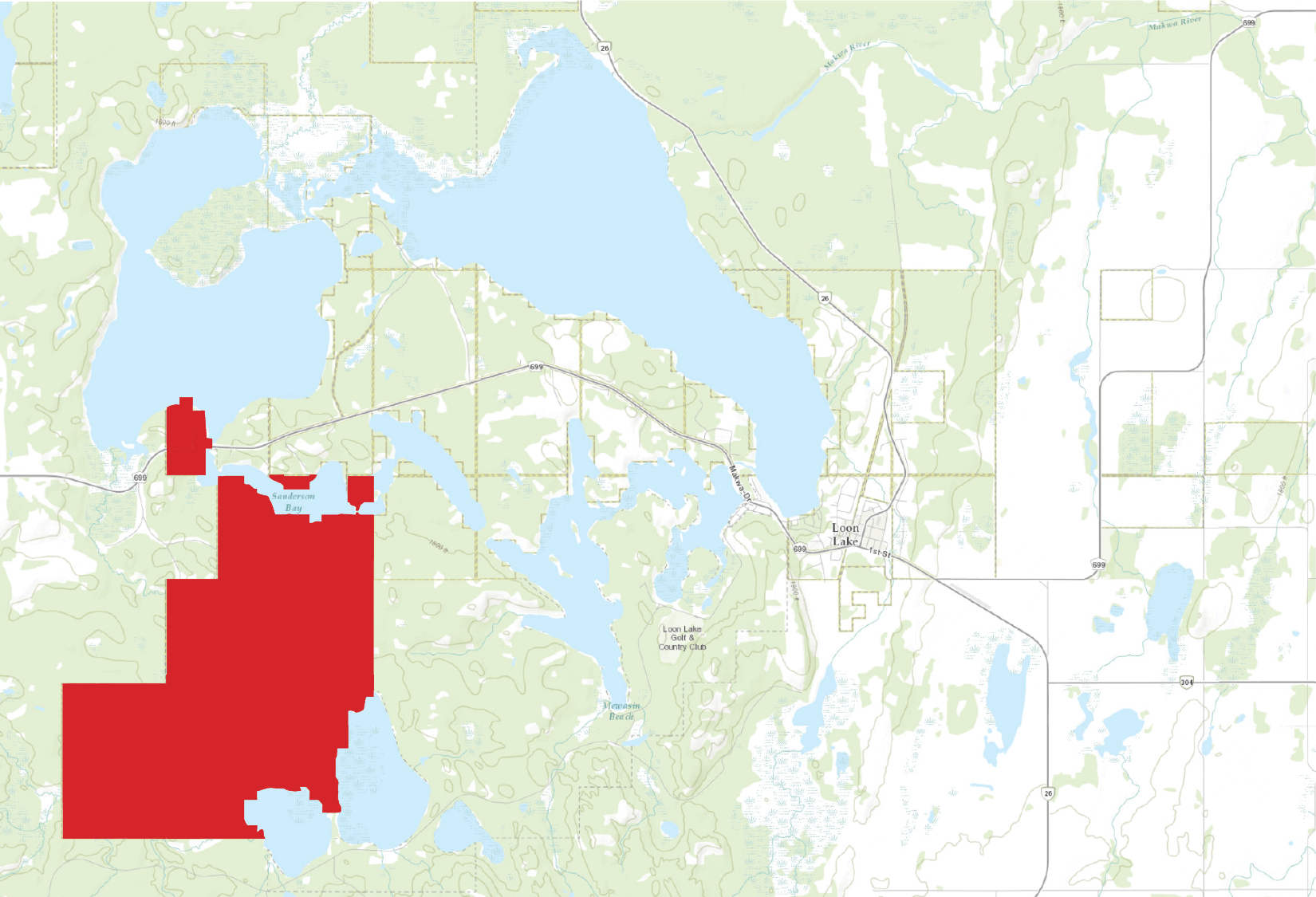

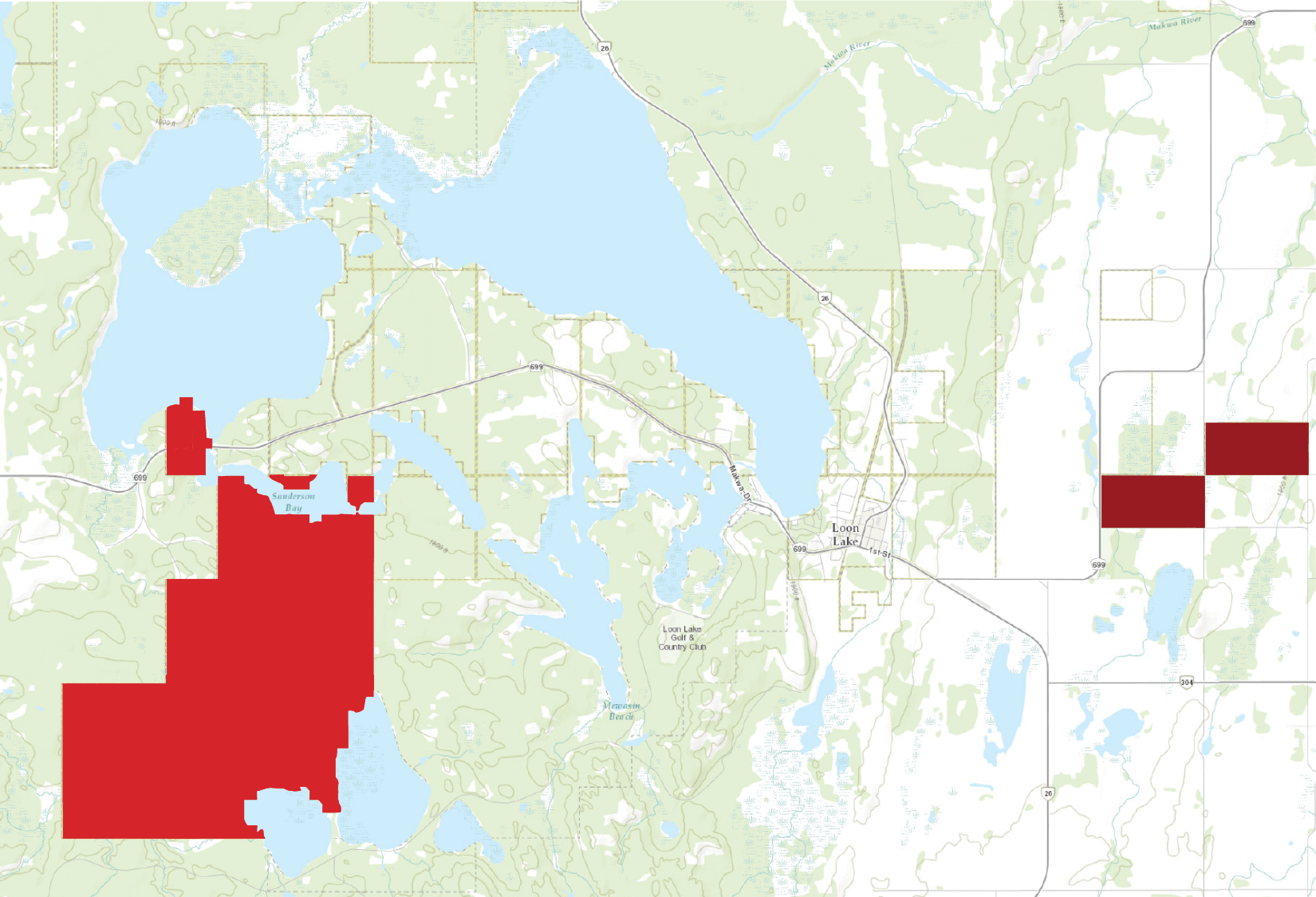

Makwa 129 and Makwa 129a

Canada officially identified and set aside our reserve they called Makwa 129. It was located at Goose Lake. We would have access to water at Goose Lake. It included the west side of Peepeekoot Crossing where the last battle of the 1885 Resistance happened.

But none of the land they wanted to give us as Makwa 129 was suitable for hayfields. We told Canada we needed hayfields for crops and our animals. We needed more suitable land included in our reserve.

Canada responded and set aside two small unconnected parcels east of Makwa Lake as our hay fields. At first Canada only thought they were going to lease these lands for us. But then they called these two small parcels Makwa 129a. It didn’t make any sense to us.

Makwa 129 and Makwa 129a together was 5,129 acres. This was enough reserve land for only 40 people.

Makwa 129b

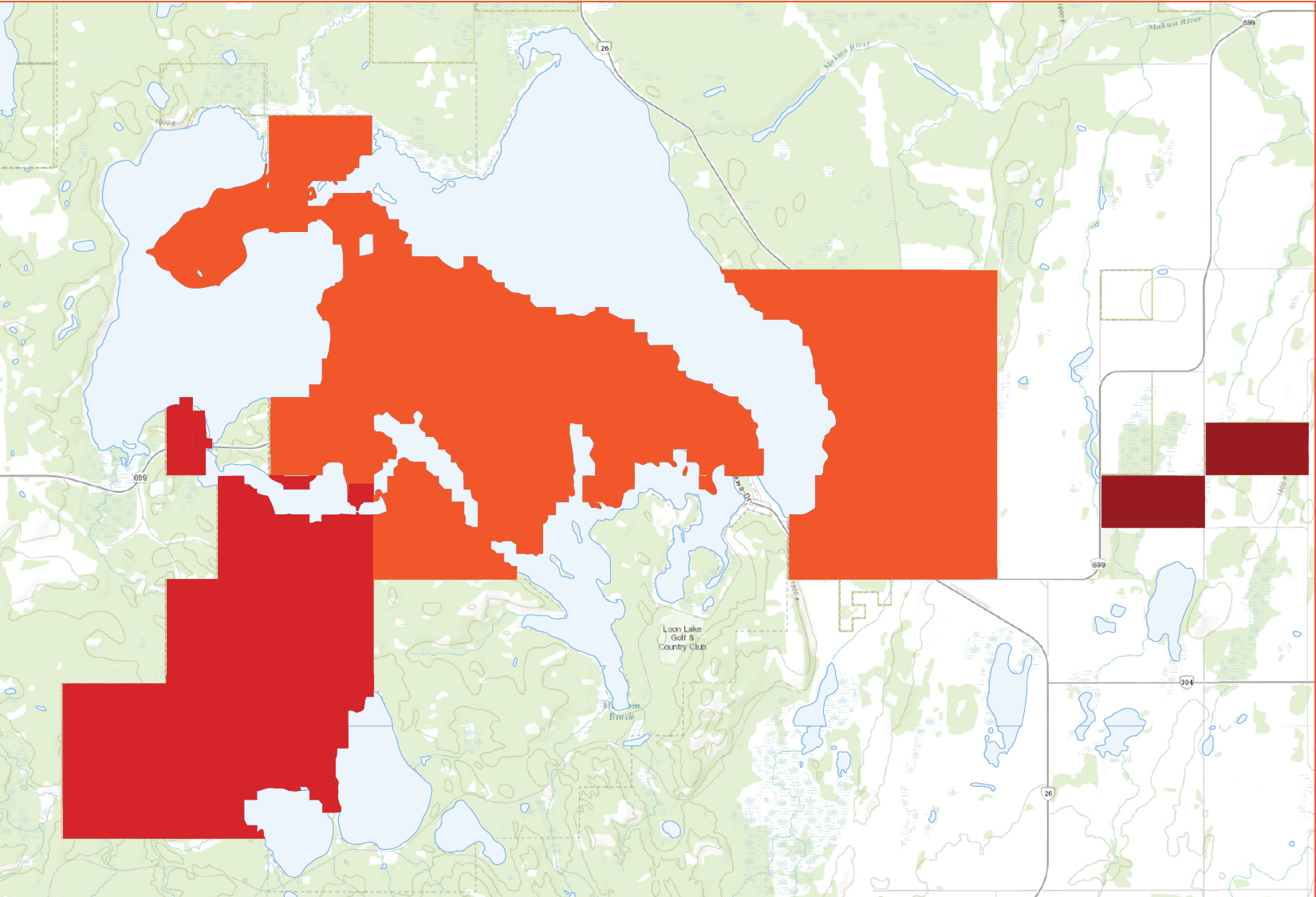

In 1930, 70 more Makwa Sahgaiehcan entered or took treaty. Canada had a problem. When they went to set aside more reserve land for 70 more Makwa Sahgaiehcan people, 10,000 acres would be needed.

On August 5, 1930, Canada officially set aside another 9,247.3 acres for the Makwa Sahgaiehcan. They called it Makwa 129b. Using the Treaty 6 formula of 128 acres per person, this was enough land for 72 more Makwa people.

By 1930 many moniyawak had come into our area and claimed land for themselves.

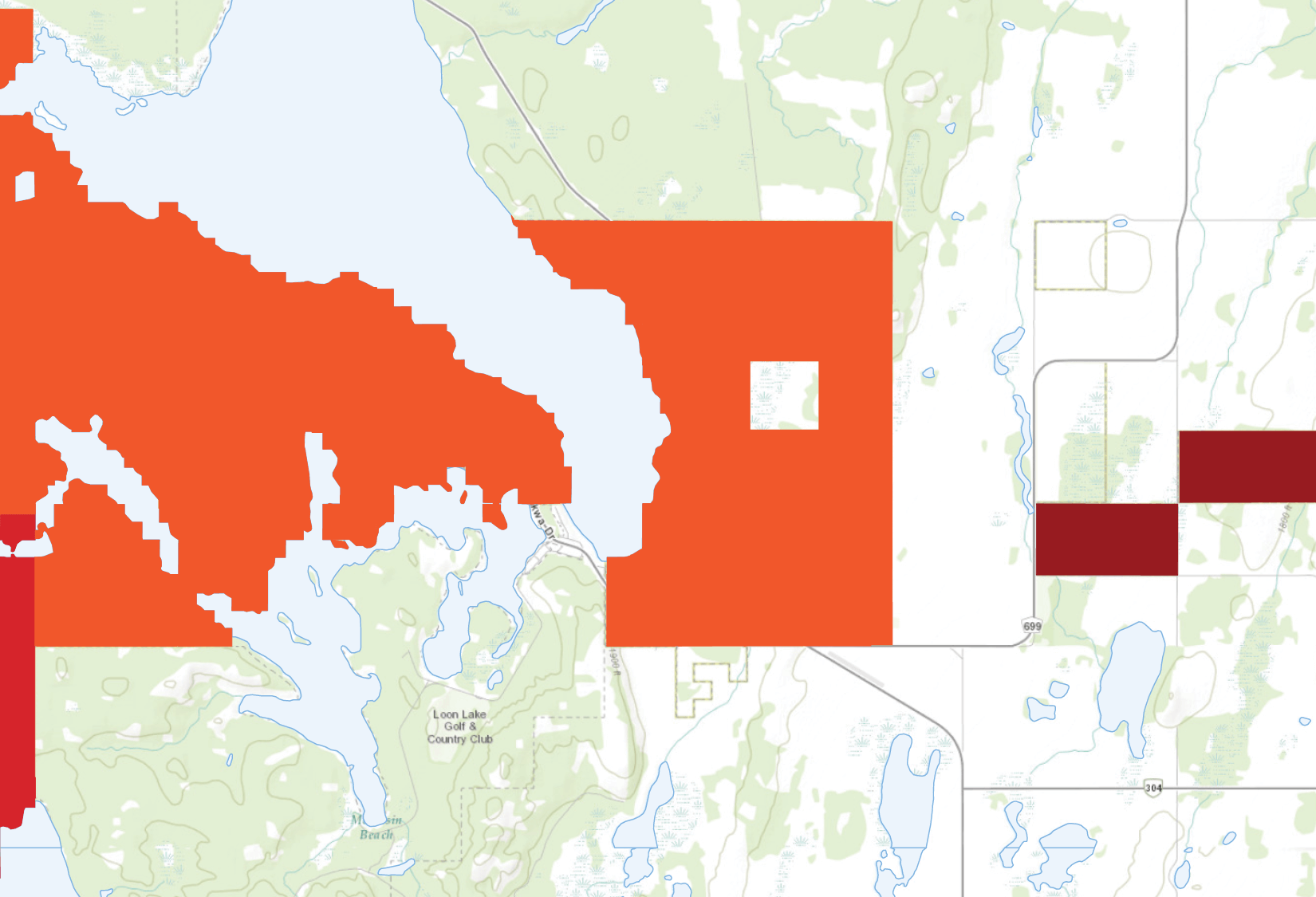

They surveyed Makwa 129b around a moniyaw. Rather than ask him to leave, Canada surveyed around him, leaving a big hole in the center of Makwa 129b.

We didn’t agree with the way Canada surveyed our reserves and kept some lands for themselves.

- Our reserves didn’t reach the shoreline of our lakes, preventing our access. Canada used straight lines, rather than the lake shores. They even missed an entire island.

- Our reserves were crisscrossed with undeveloped road allowances.

- Our reserves were bisected by provincial roads, running right down the middle.