It Wasn’t Education

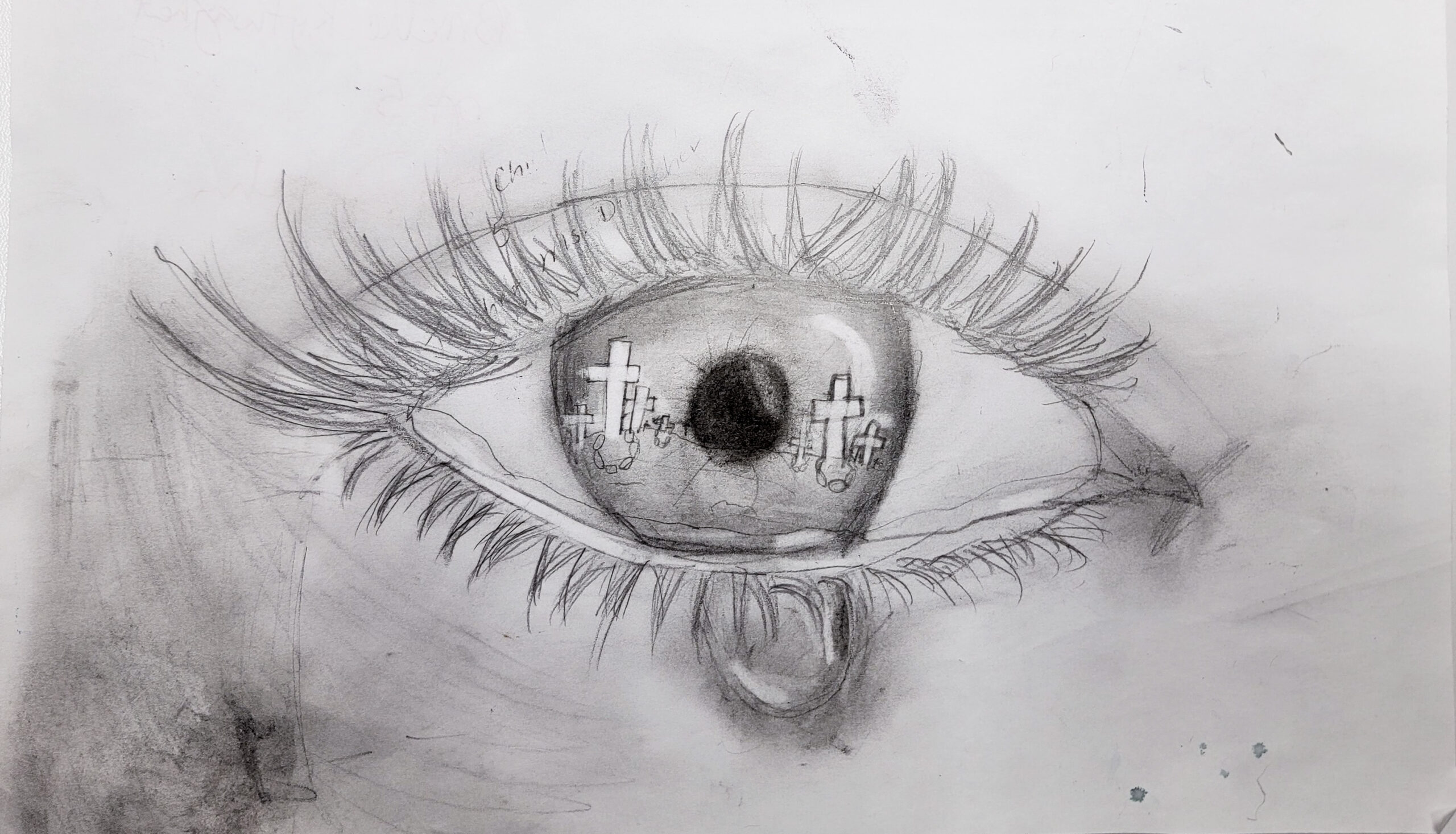

Art by Brielle Kytweyhat

We understood there was a treaty promise of free education for children paid for by Canada.

First Nations who signed treaty thought their children would receive a good education that would prepare them for the future. This was one of the reasons many First Nations thought signing treaty would benefit them. This could not be further from the truth.

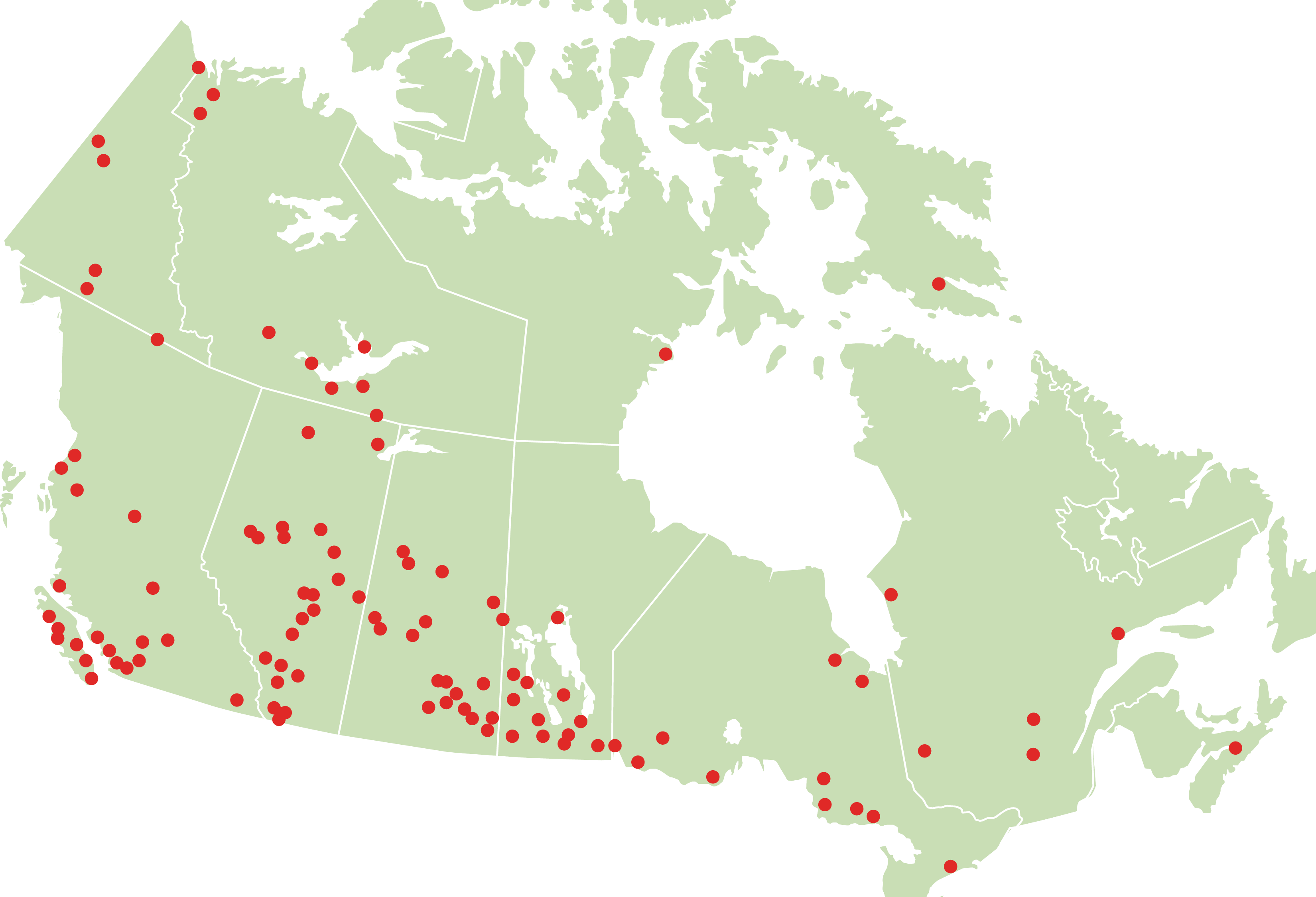

Residential Schools were a system of cruel institutions across Canada meant to force Indian children to become white.

The idea for Residential Schools came from church leaders, who thought that the best way to convert Indian children would be to set up boarding schools. Indian children would spend months away from their families and communities at these horrible places.

Residential Schools were probably the worst place children could be. Instead of teachers, the schools were often run by anointed members of the church, like nuns and priests. These people did not care about the children in their care, and in many cases, hated them for their Indian identity and culture. Children at Residential school were abused and faced conditions similar or worse to prisons. Starvation, disease, physical and sexual abuse were common.

Children did not receive a good education. Instead of preparing them for the future they were forced to learn how to be white, and that they should be ashamed of their identity and culture.

Children who went to Residential School had a one-in-four chance of dying.

Makwa Sahgaiehcan children went to many Residential Schools including:

- Beauval (Ile a la Crosse) Residential School

- Lebret (Qu’Apelle) Residential School

- St. Paul’s (Blood) Residential School

- Sarcee (St. Barnabas) Residential School

- St. Michael’s (Duck Lake) Residential School

- Thunderchild (St. Henri) Residential School

At its height, in 1931, there were more than 80 residential schools across Canada.

The effects of Residential and Day Schools are still felt by survivors and their families to this day.

We know from our Elders that Residential Schools deeply affected our lives.

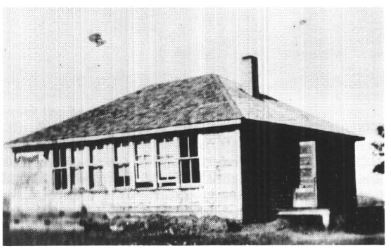

Town of Loon Lake Day School. Photo by Hinchsliff.

First Nation parents learned quickly Residential Schools were not what was promised. Many tried their hardest to keep their children from going far away to these institutions.

There are many Makwa Sahgaiehcan people who did not attend school at all because their parents did not want them to go to Residential School. They hid their children in the bush or on the trapline.

In addition to Residential Schools, Canada also set up schools on reserves but still run by Canada and the churches. Unlike boarding schools, these schools meant children could go home at night. There were almost 699 of these types of schools in Canada. By 1920, parents had no choice but to send their children to this type of school.

These schools were called Day Schools.

Day Schools were usually one-room buildings, with all grades learning together. It was almost worse than Residential Schools, because when children went home at night, they faced conflicts with their families. The curriculum that was taught was substandard.

For Makwa Sahgaiehcan, the fact there was a white town in the middle of our reserve lands with a school for white kids let Canada off the hook. Canada didn’t want to build a Day School on Makwa Sahgaiehcan reserve lands. Canada did not want the expense of building a school on our reserve for only Makwa students.

Ernie Studer School 2023

In 1949, a new school was built for the white children of the Town of Loon Lake. Over the next ten years, the Loon Lake Central School was expanded several times to make room for the expanding population of the Town of Loon Lake.

Canada used funds meant for Makwa Sahgaiehcan education to rent out the old school building from the Town of Loon Lake to use as a Day School for the children of the Makwa Sahgaiehcan First Nation as “an experiment.” Canada hired a teacher from the Town of Loon Lake and opened the Loon Lake Day School.

For 20 years, Makwa Sahgaiehcan children attended the Day School located in the middle of the Town of Loon Lake. Many children had bad experiences. But then it got worse.

By 1969, Canada did not want to pay for Residential or Day Schools anymore. They started the process of closing down or transferring school administration to First Nations themselves.

But again…not for Makwa Sahgaiehcan First Nation.

Instead of building a separate school for Makwa Sahgaiehcan children on our reserve that we would control, Canada decided to close the Day School in Loon Lake and partially fund a public school in the Town of Loon Lake for both white and Indian children.

This was Ernie Studer School. It was named after one of the first white settlers to squat in the Town of Loon Lake.