They called us Stragglers

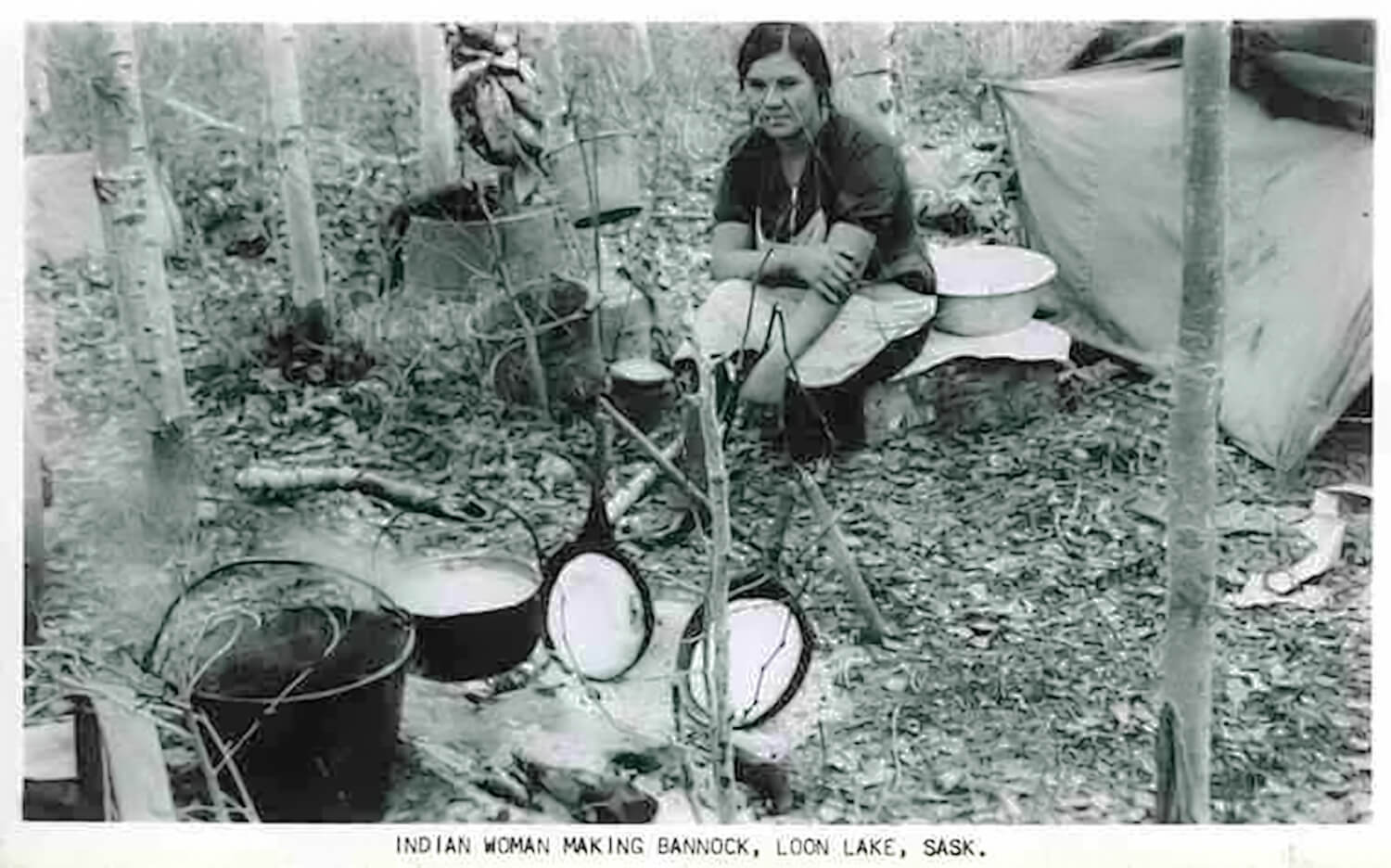

Unknown Makwa Sahgaiehcan Woman, 1940

Cree leaders, like Ahtahkakoop and Mistawasis, signed Treaty 6 in 1876 on behalf of their respective communities. Their reserves were officially identified and set aside right away by Canada.

However, getting all Cree people to accept or enter treaty and move onto reserves was a complicated process for Canada. There were many people who were not at Fort Pitt or Fort Carlton during the summer of 1876 when Treaty Commissioners were there. Others were there, but Canada failed to keep proper track of their names.

Canada did not have a good understanding of how Cree peoples were organized or who spoke on our behalf. There was even confusion amongst Canada Indian Agents that Island Lake (Ministikwan), Big Island Lake (Joseph Big Head) and Loon Lake (Makwa Sahgaiehcan) were different places with different groups of Crees. Canada did not even recognize a Makwa Sahgaiehcan Chief until 1936.

In the early years following the original signing of Treaty 6 in 1876, we continued to move between reserves, either to live or visit for long periods of time.

But many Cree people chose to not sign or enter the treaty. It was clear to us once a family moved onto the reserve and ‘took treaty’, they could not live the same life they had always lived.

“Stragglers” was a term invented by Canada for people who were reluctant to ‘take treaty’ and move onto a reserve. Canada called Makwa Sahgaiehcan people “stragglers.”

For the early years following the original signing of Treaty 6, some of us didn’t want to accept treaty or live on the tiny pieces of land they told us was our reserve. Some people lived on a reserve but were not officially part of a Band. Some people accepted the $5 treaty payments without officially added to a treaty paylist.

There were good reasons for not accepting the treaty Canada was offering. We heard from some of our relatives who lived to the east of us that once you signed a treaty, Canada took your children away, sometimes very far away, to live in Residential Schools. Some people said they continued to starve even after signing Treaty 6 because people didn’t get the assistance promised under Treaty 6.

For those of us who still travelled and lived on the land, Canada increased the pressure on us to take or enter treaty and move onto a reserve. Because of that pressure, more and more people took treaty. But many of us wanted to continue our way of life on the land.

As more and more settlers came into our territory, Canada thought we were getting in the way. For those of us still living our lives off reserve, they called us ‘hunting Indians’ or ‘heathens.’ We stood in the way of settlers. Canada decided to get us off the land.

Before the boundaries of Treaty 6 was identified, Makwa Sahgaiehcan territories stretched from the North Saskatchewan River, south to Cypress Hills into what is now the United States, from the Rocky Mountains east to Hudson Bay. But we always knew Makwa Lake and Goose Lake was our home.

Makwa Sahgaiehcan people are not mentioned in Canada’s records before 1898. Canada didn’t bother learning about us. We were sometimes referred to as “Loon Lake Band” or “Makwa Lake Band” or even “Wood Cree at Loon Lake”.

We are deeply connected to other Cree peoples in our area. All Cree peoples, including Makwa Sahgaiehcan moved freely between communities, whether through marriage, adoption or cooperation.

Makwa Sahgaiehcan have family at Thunderchild, Waterhen, Big Island Lake (Joseph Bighead), Ministikwan (Island Lake), and Onion Lake (Seekaskootch/Makaoo). We were all connected.

When the Onion Lake reserve was surveyed and set aside in 1879 for Chief Seekaskootch, Canada put other First Nations in the same place, on the same reserve. Some of Makwa Sahgaiehcan people were grouped under Onion Lake (Seekaskootch), Ooneepowhayo (Frog Lake) and Waterhen. Some of us are even on early treaty annuity paylists at Onion Lake.

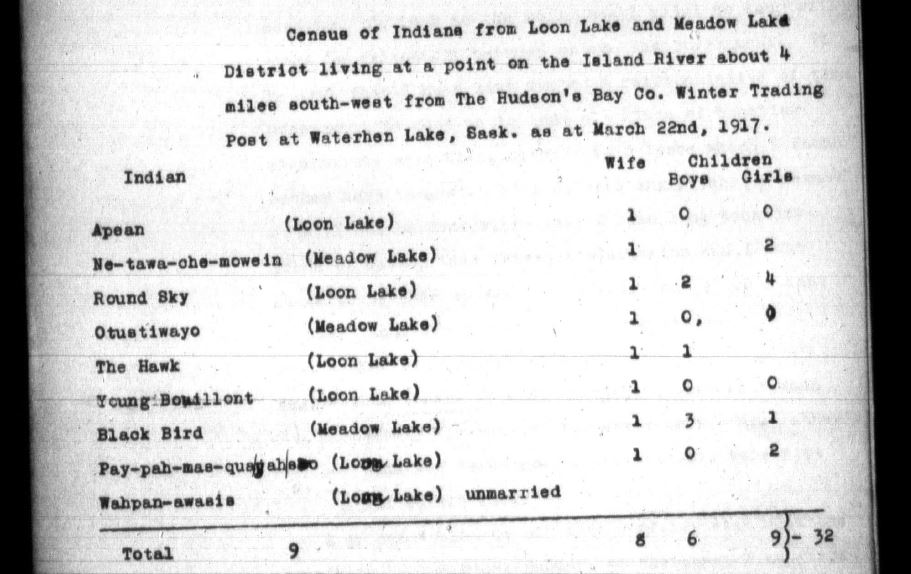

Paylist, 1917

It was easier for Canada if all “Indians” lived on one big reserve. We would be easier to control. That would only require one Indian Agent, one Band list, one annual Treaty payment. Especially in our area, Canada wanted everyone to live together at Onion Lake. By 1913, Canada said there were 250 Crees were in the area, and they wanted us all to be on one reserve. We never wanted that.